Julius Röntgen and Edvard Grieg

Röntgen with Edvard and Nina Grieg, Amsterdam 1897

In 1883 Edvard Grieg came to Holland for a number of concerts in which he featured as the soloist in his own piano concerto. Röntgen en Grieg had already met each other once before in Leipzig and Grieg’s visit to Holland provided an excellent occasion for Röntgen to invite him to come and stay in Amsterdam. Grieg accepted the invitation replying: “I look forward to seeing you and your wife again; make sure that one day lasts 48 hours!” Grieg’s stay at the Röntgens would not last one day, but one month. Thereafter, both musicians were connected by a warm bond of friendship which would last 24 years, until Grieg’s death in 1907.

In the Grieg-biography written by Röntgen (published in 1930) he recounts his first meeting with Grieg in 1875:

“I met him for the first time at the ‘Skandinavisk Selskap’, an association of young Scandinavian artists, mostly musicians who were studying at the Conservatory in Leipzig. Grieg was among the listeners. I played with Amanda Maier: a violin sonata written by her. Grieg listened carefully, I can still see him sitting there in his velvet jacket, brief and decisive in his expressions, everything about him highly rhythmic, though softened by his blue expressive eyes.”

During his visit to Holland in 1883 Grieg stayed with Röntgen in his house in the Van Baerlestraat. After a long and tiring concert tour through Germany he had arrived in Holland exhausted, but during the weeks thereafter the Röntgens gave him every opportunity to recover. After his stay in Amsterdam Grieg left for Italy, where he remained four months.

In July 1884 Röntgen paid his first visit to Norway. In the end he would go and see Grieg a total of 14 times, usually during the summer holidays. Together with Grieg and his friend, the lawyer/musician Frants Beyer, he undertook long and adventurous hikes in the Norwegian mountains of Jotunheim.

View of the fjord from Troldhaugen, Grieg’s house near Bergen.

Röntgen writes about this:

“Jotunheim is a world entire unto itself, merely inhabited by shepherds in summer. Grieg and I travelled from Lofthus by “stolkjärre”, a small cart on two wheels, to the Sognefjord from where we reached Skjolden by rowing boat. On the way we took a minstrel and his Hardanger violin with us in our cart and he played us his music for the rest of that wonderful journey. How this music goes with nature. Grieg listened, enchanted, a glass of port in his hand which he would offer to the minstrel every now and again. “That is Norway “, he said. It was a warm August afternoon, the fjord a deep green and we, stretched out on bags of hay, let the magnificent mountain scenery pass us by.”

Back in Amsterdam Röntgen received the following letter from Grieg:

“And now we are both back in our own houses and thinking of those beautiful snowy plains and glaciers. Your sympathy for my country and everything connected with it is quite unique and since this summer you have captured a special place in my heart. As rather trivial evidence of this please allow me to mention your name with my newest piano works.”

The piano works alluded to here are the 5th series of Lyrical Pieces (op. 54), of which, in all, ten volumes were published. The 9th volume, op. 68, includes Abend im Hochgebirge, initially written for the piano, but later arranged by Grieg for the oboe, French horn and string orchestra (or piano).

Röntgen too let himself be inspired many a time by his trips through Norway. Many titles of compositions bear witness to this, but the work Aus Jotunheim, a suite for violin and piano with melodies Röntgen heard a peasant woman named Gjendine sing in a remote mountain hut, does so in particular. Her way of singing appears to have made a great impression on Grieg as well as Röntgen. Grieg incorporated these songs in his Norwegian folk songs, op. 66, as well as in other works, whereas Röntgen later arranged his Jotunheim-suite for French horn and piano and also for orchestra. The original version (violin/piano) he sent to Grieg in 1892 on the occasion of his 25th wedding anniversary. To thank him for this, Grieg writes:

Villa Troldhaugen

“The Jotunheim pieces have given me tremendous pleasure. Apart from being extremely interesting for us “Jotunologists” I find them beautiful and very poetic. Now all I want is for you to perform them for me.”

It wasn’t until 1897 that Grieg visited Holland again. Röntgen took the initiative to organise a number of concerts and from 1896 onwards there was a great deal of correspondence about the programme and the organisation. The concerts in February were a huge success. Grieg conducted the Concertgebouw Orchestra for the first time and performed during a chamber music soirée in which his wife, Nina Grieg, and Röntgen also had a part. There were more concerts in The Hague, Utrecht and Arnhem, but during the entire period the Griegs stayed with the Röntgen family. Röntgen writes in his Grieg biography:

“One evening I came home from the Conservatory and found my music room festively lit, Grieg at the grand piano playing his Hochzeitsmarsch. I did not understand the reason for this joyous reception, until I realised that Grieg was playing not my old grand piano but a completely new Bechstein which he had sent for and was now offering to me as a gift! What joy my surprise brought him. The evening was concluded with oysters and champagne.“

Eating oysters in restaurant ‘Die Port van Cleve’ in Amsterdam, usually after a concert, was a set ritual whenever Grieg was in Holland.

Grieg’s acquaintance with the Concertgebouw Orchestra would soon have a follow-up: in the Summer of 1898 Bergen was to organise a big fishing- and industrial exhibition. Grieg wanted to organise music festivities to go along with this and to invite the Concertgebouw Orchestra for the occasion. Röntgen liked the idea and offered to act as a mediator. The Concertgebouw Orchestra was willing to come, but the committee of organisers in Bergen appeared to resist the cooperation of a foreign orchestra to a Norwegian music fest. Grieg was most indignant about this and defended his intentions with a letter of protest, in which he wrote that it does not matter if Norwegian music is performed by Chinese, Japanese or Dutchmen, as long as it is performed well and that, after all, Norwegian orchestras are made up of mostly German musicians anyway.

To make matters worse, Röntgen lets him know that he will not be able to make an appearance himself due to examinations at the Conservatory. Grieg writes:

“You can’t come? Scandalous! Let’s leave it at that. I might not be there either. I will probably have died before then. Because I will not be able to take these nights of insomnia much longer. I will however try and fulfill my duty… I suggest we move the music fest from Bergen to Bergen op Zoom and that you take over!”

Despite all the vicissitudes the Music Fest in Bergen did, after all, take place in June 1898. The first foreign tour of the Concertgebouw Orchestra was a great success. Grieg writes to Röntgen:

“The enthusiasm is boundless. I think I can safely say that nowhere and never has an orchestra been cheered as much. Every day, if there was time, festivities. The farewell was one as is only possible in Bergen. After the last festivities in the Concert Hall everyone made for the quay to say goodbye to the orchestra. It was one o’clock at night. More and more people from Bergen joined in, the military band in front. In the end, there must have been at least 10,000 people.”

During the following years Röntgen would visit Grieg regularly, sometimes with his family, sometimes with others, such as the singer Johannes Messchaert. In 1902 Röntgen’s fourth son was born, named after Grieg and Beyer. “But”, writes Grieg, “how can such a musical family bear such an unmusical sound? The theme works much better as an inversion: Frants Edvard.”

To prove his point, what follows is an entire explanation with several musical examples which show that the rhythm inversion does in fact go much better with certain themes and motives in Grieg’s work. When in 1904 another son is born this child is named in the proper order: Frants Edvard. Röntgen reports to Grieg by letter:

“Yesterday our son was born. Everything went molto presto e leggiero. This time we would like to call him Frants Edvard to make up for our last “Declamationsfehler”. Long live the double counterpoint of our friendship!”

One year later, in 1905, Röntgen celebrated his 50th birthday. He received an album with contributions from friends from all over the world. Grieg sent a short composition: “Sehnsucht nach Julius “. This attractive little piece was later published with the title Resignation, as part of his last pianowork Stimmungen op.73. In that year Grieg hardly managed to compose anything at all. He empathised a great deal with the political developments in his country which would ultimately lead to independence for the kingdom of Norway. In 1907 Grieg and Röntgen were invited by King Haakon VII to the royal manor house in Christiania. They gave a concert there together and during this occasion Röntgen was awarded the Order of St. Olaf. Nina Grieg also performed; it was the last time she and Edvard played for public together. Grieg grew steadily weaker and knew the end was near. That same year Röntgen visited Troldhaugen for the last time. Grieg felt suddenly better, also because Percy Grainger, the Australian pianist whom he had met shortly before and whose interpretation of his piano music gave him much joy, joined them. Grainger broke new ground with his reseach regarding folk music in English speaking countries with the aid of a phonograph. Grainger, Grieg and Röntgen became best friends immediately. But for Grieg the end was nearby. It was with great sadness that Röntgen finally said goodbye to Grieg, knowing that they would probably not see each other again. Shortly afterwards Grieg died, on 4 September 1907.

Even after Grieg’s death Röntgen continued to dedicate himself to his friend’s music. Nina Grieg sent him a substantial number of posthumous works, wondering if they were fit for publishing. Among them was a string quartet from 1891, put aside by Grieg and never finished. Röntgen loved the work and took it upon himself to finish it and to have it published. He writes to Nina Grieg about how the work is received at its first performance in the Röntgen household:

“You ought to have been with us last night. We played the quartet. A strange sensation that Edvard never heard it himself. Our set-up was very original: Harold Bauer, the great pianist, played 1st violin and he did so very well indeed. Casals played 2nd violin and held the instrument between his knees like a cello, me on the viola and Mrs Casals – excellent – on the cello, all four of us with the utmost enthusiasm, my wife the only one in the audience.”

The biography of Grieg by Röntgen was published in 1930. Memories the writer has are alternated with fragments from letters from Grieg himself making Grieg speak to the reader directly by way of his letters, carefully selected by his biographer and close friend. In 1993 the book came out in Norwegian on the occasion of Grieg’s 150th birthday.

The extensive letter exchange between Grieg and Röntgen was published in 1997 by the Koninklijke Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis:

The extensive letter exchange between Grieg and Röntgen was published in 1997 by the Koninklijke Vereniging voor Nederlandse Muziekgeschiedenis:

Finn Benestad and Hanna de Vries Stavland: Edvard Grieg und Julius Röntgen, Briefwechsel 1883-1907 (KVNM, Utrecht, 1997).

This correspondence makes for a unique document in which the composers remark candidly upon works by themselves or others and report about their colourful experiences on a musical, social or political level. More than two hundred letters, postcards and telegrams written by Grieg are in the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag (Municipal Museum The Hague), whereas the 176 letters Julius Röntgen wrote are kept in the Public Library in Bergen. A few of Röntgen’s letters have been mislaid, presumably during Grieg’s international travels.

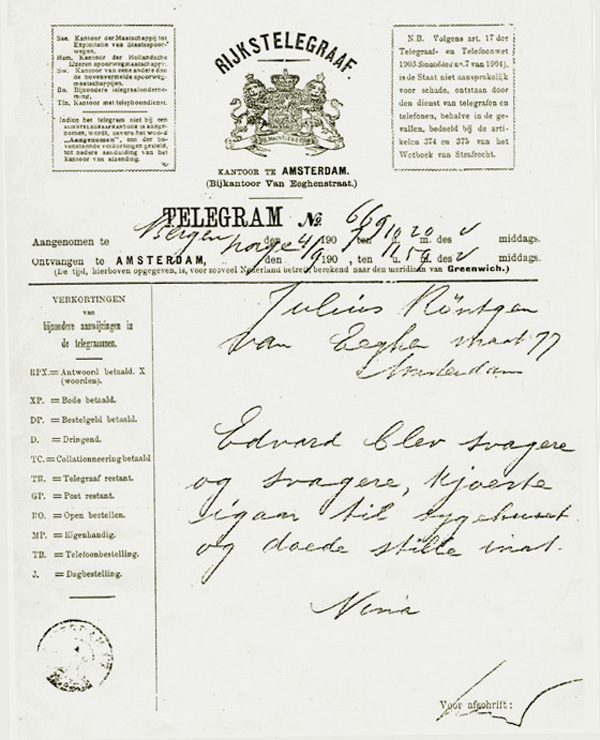

Telegram from Nina Grieg, 4 September 1907, after Grieg’s death. “Edvard grew steadily weaker, was taken to the hospital yesterday and died peacefully last night “.