International friendship ties

by Emile Wennekes

Julius Röntgen was accustomed to associate with musicians of international stature and of musicological importance from a very early age. His parental residence in Leipzig was a va-et-vient of prominent musicians.

As the son of a Dutchman and a German-French mother, young Julius had the blood of three nationalities running through his veins from the very start. His father, Engelbert, was leader of the famous Gewandhausorchester, his mother Pauline (née Klengel) a meritorious pianist and daughter of the solo cellist of the Gewandhausorchester. She – as a proud mother – introduced the talented Julius into the international music world; together they visited Franz Liszt in 1870. After fruitless waiting in Weimar for the messenger to herald the news that The Great Liszt was at last able to see him, Röntgen decided to take matters into his own hands and to penetrate into the bastion of the charismatic composer and pianist of his own accord. He did so successfully. When faced with Liszt Röntgen asked him carefully when would be a good time to play him something. “Now”, Liszt replied. “Be seated!”. And that is exactly what happened. Liszt seemed much taken by his diminutive colleague’s own compositions and by his piano playing. At every measure he would fire off a new and well-meant compliment.

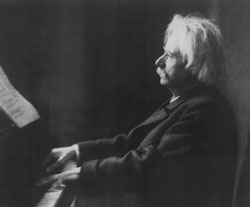

Edvard Grieg

Edvard Grieg

In Rome, several months before, another young musician had auditioned for Liszt: Edvard Grieg (1843-1907). Röntgen and Grieg developed a close friendship, based on kindred spirits, aesthetic preferences and mutual respect. Griegs visit to Holland in 1883, now Röntgen’s country of residence, meant the beginning of a series of visits back and forth. The friendship has been documented in an extensive correspondence and by a biography with a personal touch which Röntgen would write about him in 1930.

Johannes Brahms

Postcard from Brahms 22 April 1896

Röntgen manifested himself in Amsterdam as a true Grieg-apologist by devoting himself passionately to his music and performing it tirelessly. More or less the same can be said about Röntgen’s feelings towards the music of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). In 1884 Brahms visited Amsterdam in order to conduct his Third Symphony and his Piano concerto in B flat. Röntgen had the honour to be elected as the soloist. For Brahms however, the performances turned out to be a disappointment; before the Concertgebouw Orchestra was founded Dutch orchestral culture had hardly reached a professional level, let alone the level of the international standard to which Brahms was accustomed. Nevertheless, some years later Röntgen tried to persuade Brahms to come to Amsterdam again for a series of chamber music concerts. Brahms felt sympathetic towards Röntgen. When writing about Julius to Clara Schumann at the end of his life, he says that it fills him with ‘pleasant and benevolent feelings’. Brahms commends Röntgen in his capacity as accompanist to singer Johannes Messchaert; he had not come upon a piano part played with so much love before.

Johannes Messchaert and Julius Röntgen. Dr. Otto Böhler Schattenbilder.

Moreover, he praises Röntgen as having a unique and very sweet character. “He has always “, writes Brahms in 1895, “remained a child, so innocent, so pure, open, enthusiastic and with his particular naive and nervous manner”.

Illustrious list

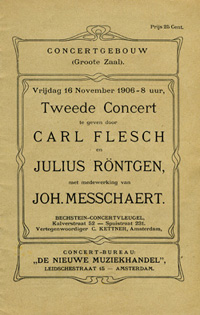

According to international testimonies, Julius must indeed have had a captivating personality, well-spoken, especially when engaged in musical conversation. He reminded violinist Carl Flesch(1873-1944) of a typical German professor: “thickset, stout, near-sighted, absent-minded, comical and entertaining “. “Almost everyone “, observed Flesch, “wanted to be his friend: Grieg, Brahms, Casals, Tovey, Grainger”.

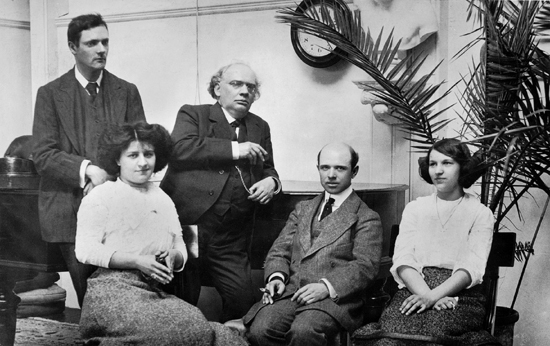

Clara Schumann, violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim, the singers Julius Stockhausen and Johannes Messchaert and many other distinguished people may be added to this illustrious list. Carl Flesch wrote at the end of his life that Röntgen was the musician to whom he could relate most; in his memoires he devotes a good many sentences to his beloved friend. On the recommendation of Röntgen the Hungarian Flesch was violin professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam, which Röntgen co-founded, from 1903 until 1908. They played chamber music together for twenty years. They also regularly formed a trio with the Spanish cellist Pablo Casals(1876-1973). Shortly before the turn of the century Röntgen wrote a cello concerto as well as three cello sonatas for Casals. These they performed during international tours, earning approval in Paris especially. Casals and Röntgen too became very close; Röntgen’s sons Engelbert and Edvard Frants both studied with Casals and Julius Röntgen was one of the first to hear about Casals’ ambitious plans to form his own symphony orchestra, the Orquestra Pau Casals.

Clara Schumann, violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim, the singers Julius Stockhausen and Johannes Messchaert and many other distinguished people may be added to this illustrious list. Carl Flesch wrote at the end of his life that Röntgen was the musician to whom he could relate most; in his memoires he devotes a good many sentences to his beloved friend. On the recommendation of Röntgen the Hungarian Flesch was violin professor at the conservatory of Amsterdam, which Röntgen co-founded, from 1903 until 1908. They played chamber music together for twenty years. They also regularly formed a trio with the Spanish cellist Pablo Casals(1876-1973). Shortly before the turn of the century Röntgen wrote a cello concerto as well as three cello sonatas for Casals. These they performed during international tours, earning approval in Paris especially. Casals and Röntgen too became very close; Röntgen’s sons Engelbert and Edvard Frants both studied with Casals and Julius Röntgen was one of the first to hear about Casals’ ambitious plans to form his own symphony orchestra, the Orquestra Pau Casals.

Julius Röntgen with

Donald Tovey, Pablo Casals en de Hungarian violinist Jelly d’Arányi, and others, 1911.

Another violinist with whom Röntgen had been friendly from a very early age was the legendary Joseph Joachim (1831-1907). Joachim was sure that Röntgen could turn out to be one of the ‘great masters’ in music history. Not surprising: Röntgen had already performed together with Joachim at the tender age of fourteen. This performance, during the Rheinische music feasts in 1869, made The Times. Röntgen was not entirely able to redeem the great promise then shown. Music teacher Alfred Richter from Leipzig attributed this to Röntgen leaving for Amsterdam. Perhaps, Richter suggested in his memoirs, Röntgen would have developed himself better within the surroundings of his home town instead of in the cold wet foggy climate that this country bordering on the North Sea had to offer. Nevertheless, even when advanced in years Röntgen was discovered again and again by new generations and even appreciated many a time as a progressive composer.

Dr. h.c. Julius Röntgen,

Edinburgh, 27 maart 1930

The Australian-American pianist, composer and collector of folk music Percy Grainger wrote in a letter how in the past he had made himself popular especially ‘by playing new works’, by, among others Grieg, Debussy, Ravel, Albeniz, Röntgen, Cyril Scott and Balfour Gardiner. Percy Grainger (1882-1961) belonged to a younger generation and had a predilection for Scandinavian culture and its inhabitants. Grainger was one of the first folk song collectors to use the phonograph for his transcriptions. When he first met Röntgen at the Griegs in Troldhaugen in 1907 he appeared to be remarkably well acquainted with Röntgen’s music. Röntgen, in turn, was impressed by the young man: he designated him as a ‘folkloric genius’.

From England too signs of appreciation came Röntgen’s way. Donald Francis Tovey (1875-1940), at that time a musicological legend and a great musician, with whom Röntgen frequently performed, was the person who initiated Röntgen’s honorary doctorate at the University of Edinburgh in 1930. Röntgen at the time was 75 years old. He did not deliver a speech upon receiving de honoris causa-degree certificate; he hardly spoke the English language. As a token of his gratitude he dedicated a symphony to the town, the Edinburgh Symphony. He proffered the score during a ceremony in the old main building of the University on 27 March 1930. Later that year the symphony was performed for the first time by the Unversity Orchestra, The Reid Orchestra, conducted by Donald Tovey.